Saltash History and Heritage

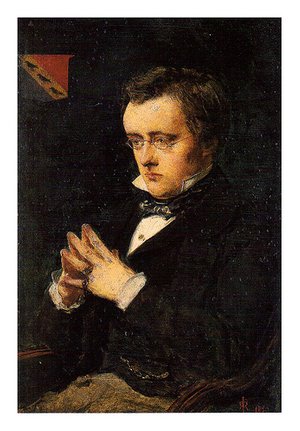

Wilkie Collins

The Victorian writer, Wilkie Collins, is not as famous as his friend Charles Dickens, but his literary reputation is equally high. Two of his novels, The Woman in White and The Moonstone, have been continuously in print since they were first published in the 1860s. They are generally considered to be the first mystery and detective novels written by an English author.

Wilkie Collins did not confine himself to fiction. We in Cornwall are grateful to him for the book Rambles Beyond Railways, which is based on a walking tour of the county he made in 1850 (at the age of 26). It contains some marvellous descriptive writing. One of the highlights is his visit to Botallack Mine, near Land's End.

The first modern edition (with an introduction by Ashley Rowe) appeared in 1948; it was a reprint of an edition published in 1861. Its first chapter commences with Collins already well into Cornwall, at LoBut in the First Edition, published in 1851, Collins started the book with an account of his entry into Cornwall – by boat. Perhaps its element of larkiness and its concentration on one person were considered not to match the style of the rest of the book. At any rate, Collins dropped the original first chapter from the 1861 edition.

Collins's travelling companion was Henry Brandling, an artist friend who did the illustrations for the book.. On a summer evening in 1850, they set off for St Germans from Devonport. This is Collins's narrative regarding their departure:

We were lucky enough to commit ourselves to the guidance of the most amusing and original of boatmen. He was a fine, strong, swarthy fellow, with luxuriant black hair and whiskers, an irresistible broad grin, and a thoroughly good opinion of himself. He gave us his name, his autobiography, and his opinion of his own character, all in one breath.

He was called William Dawle; he had begun life as a farm-labourer; then he had become a sailor in the Royal Navy; now he was a licensed waterman. He was known all over the country; he would row against any man in England; he would take more care of us than he would of his own sons. If we had 500 guineas apiece in our knapsacks, he could keep no stricter watch over them than he was determined to keep now.

It appeared to Collins and Brandling that the trip would be a straightforward one, so they set off. However, Collins filled 12 pages in describing their experiences before St Germans was finally reached. There was a snag – the tide was going out. After travelling for a considerable time, they were still in the Hamoaze. William Dawle stopped rowing, and spoke. To quote from the book again:

Resting impressively upon his oars and assuming a deplorable expression of countenance, Dawle respectfully requested to be informed whether we really wished him to "row his soul out against the tide?". If we were resolved to go on, he was ready – for had he not told us that he would row against anyone?

But he felt it due to his position as a licensed waterman, to inform us that "in three parts of an hour, and no mistake" the tide would run up, and there was a place not far off called Saltash – a most beautiful and interesting place, where we could get good beer. If we waited there

for the turn of the tide, no race-horse that ever was would take us to St Germans so fast as he would row us. In short, the point was, would we mercifully "spare his shoulders", or not?

They agreed, so Dawle continued up the Tamar. Then, said Collins:

What seemed to be a collection of mud hovels, built upon mud, appeared in sight. Shortly afterwards our boat was grounded among a perfect legion of other boats, and the indefatigable Dawle, jumping up nimbly, seized our knapsacks and handed us out politely into the mud. We had arrived at that "beautiful and interesting place", Saltash.

The only light on shore gleamed from the tavern window, and judging by the criterion of noise, the whole local population seemed to be collected within the tavern walls. We opened the door, and found ourselves in a small room filled with shrimpers, sailors, fishermen and watermen, all "looming large" through a fog of tobacco, and all chirping merrily over their cups. The hostess sat apart on a raised seat in a corner, calm and superior amidst the hubbub, as Neptune himself.

As there was no room for us in this festive hall, we were indulged in the luxury of a private apartment, where Mr Dawle proceeded to "do the honours" of Saltash, by admonishing the servant to be particular about the quality of the ale she brought, dusting chairs with the crown of his hat, proposing toasts, and other pleasant social attentions.

Dawle then asked if he might now go and fetch his "missus", who lived hard by. She was the very nicest and strongest woman in Saltash, was able to row almost as well as he could, and would help him materially in getting to St Germans.

Once again, Collins and Brandling agreed, so Dawle went off to get her. Collins described the outcome:

Forthwith he did return, with a very remarkable species of "missus" in the shape of a gigantic individual of the male sex – the stoutest, strongest and hairiest man I ever saw – who entered, exhaling a relishing odour of shrimps, with his shirt-sleeves rolled up to his shoulders. "Gentlemen both, good evening", said this urbane giant (whose name was Dick), looking dreamily two feet over our heads, and then settled himself solemnly on a bench – never more to open his lips in our presence!

Our worthy boatman's explanation of the phenomenon he had thus presented to us, involved some humiliating circumstances. His "missus" had flatly refused to aid her lord and master, and had immediately gone to bed.

While they were waiting for the tide to turn, Collins and Brandling had a quick look around the town. It was brief, because as Collins explained:

The moonlight gave us very little assistance, as we groped our way up a steep hill, down which two rows of old cottages seemed to be gradually toppling into the water. Here and there, an open door showed us a Rembrandt scene – a glowing red fire brilliantly illuminating the face of a woman cooking at it, or the forms of ragged children asleep on the hearth. There were plenty of loose stones in the road, to trip up the feet of inquisitive strangers. There was plenty of stinking water bubbling musically down the kennel, and there were no lamps of any kind to throw the smallest light upon any topographical subject of inquiry whatever.

The "kennel" mentioned by Collins was the open drain that ran down Lower Fore Street at that time. When they returned to the tavern, they learned of a change in plan: in place of Dick the giant, William Dawle's son, Bill, would help to row them to St Germans. Collins continued:

So we gave the word to depart, but an unexpected obstacle impeded us at the doorway. All the women who could squeeze themselves into the passage, suddenly fell down at our feet and began scrubbing the dust off our shoes with the corners of their aprons. They informed us, in shrill chorus, that this was an ancient custom to which we must submit. Any stranger who entered a Saltash house and had his shoes dusted by Saltash women, was expected to pay his footing by giving a trifle – say sixpence – for liquor, after which he became a free and privileged citizen for life.

They got to St Germans Quay at midnight. Dawle walked the quarter-mile to the village with them. He had great difficulty in persuading the landlady of the Anchor Inn to give them accommodation, but eventually he succeeded. Here's a final quotation from that original first chapter of Rambles Beyond Railways:

Our parting with Dawle was characteristic on his side. Interpreting the right way certain convulsive motions of his arm and twitchings of his countenance, we held out our hands at a venture, and found them instantly caught and shaken with a fervour which was as physically painful as it was morally gratifying.

"Good-bye, gentlemen!" cried our friendly boatman in his heartiest tones. "You have been very kind to me – God bless you both! I should like to walk all over Cornwall with you and I would, if I could leave the missus, and get anybody to take care of my boat. Bill, boy," he said, turning to his son, "take off your hat and make a bow directly." And away he went, to row back to Saltash.

Having 'discovered' William Dawle, waterman, I looked through the 1851 Census returns for Saltash to find out more about him.

Unfortunately, he doesn't appear, either as Dawle or a variation of that surname, such as Doyle, or Dawe. This is indeed a great pity.

Nevertheless, Wilkie Collins has left us a vivid portrait of a colourful Saltash character – as well as an unflattering account of Saltash and its nightlife just over 150 years ago.

Notes and annotations by Collin Squires (Saltah Heritage)